Public Records Law applies to District Coalition, Judge announces Friday

![]()

History was made that day in the mostly empty courtroom. A lone lawyer sitting at the bar, court staff in attendance. Everyone else, even the judge, was appearing remotely. But it did nothing to dampen the impact of the ruling the judge was about to make that Friday afternoon.

Summary judgement in favor of the plaintiffs in the Hiller-Webb and Tyvoll v Southwest Neighborhoods, Inc (commonly known as SWNI) case confirmed that the district coalition was, for purposes of state public records law, a quasi-government entity and was required to turn over particular records to Ms. Hiller-Webb and Ms. Tyvoll.

As Shannon Hiller-Webb (she/hers) stated in a press release: “I am proud to represent my neighborhood and advance the goals of residents of SW Portland. I became concerned when, as a SWNI board member tasked with financial oversight, I was unable to gain answers to questions and even when submitted as a formal records request, SWNI repeatedly denied access. My intent with this lawsuit is to ensure transparency for taxpayers as the primary funders of District Coalitions who were created to serve us all.”

Associate counsel and public records attorney Alan Kessler (he/him) concurred: “It’s time for taxpayer-funded organizations doing the public’s business to provide transparency and be recognized for what they are – outsourced government bureaus.“

Marie Tyvoll (she/hers) and Shannon Hiller-Webb’s stories may have only started in the last few years, but as attorney Rian Peck (they/them) detailed in a masterclass of research and legal writing, the history behind the public records issues and the need for such transparency went back longer than even this author’s been alive, to the very founding of SWNI and the form of neighborhood/district engagement with City Council as a whole.

District Coalitions and the history of SWNI

All the way back in 1974, the state of Oregon passed SB 100, creating a statewide ‘land use planning program’, requiring cities to plan for 20 years of growth in new households and jobs. In response, the City of Portland created the Office of Neighborhood Associations, creating a conduit for residents to ‘influence land use decisions in what had previously been the political realm of the real estate industry and downtown business interests’ (Historical Context of Racist Planning: A History of How Planning Segregated Portland, p11). Unfortunately, in the first five years, while 60 neighborhood associations had been created, the power dynamics of white affluent residents having all the effective power remained.

An additional 15 years later, in 1994, City Council adopted a new plan to address issues that had emerged in the previous 1980 Comprehensive Plan, a move designed to shift away from the simple expansion of single family residences in favor of multi-family zoning. The plan was anticipated to be completed by 2005, but was quickly beset by similar failures of unequal treatment as had been seen in the Portland living situations since it’s inception.

The first community plan study outside of Central City was the Albina area, where the African American community had historically resided, and had already been torn apart by the 1948 Vanport flood and interstate expansions in more recent years, resulted in the city attempting to ‘boost economic development and bring investment and improvements to Albina’, using it as an excuse to rezone significant portions of single family residential to higher-density zoning to help meet the projected growth goals. The result, as we know well now, was to set the stage for gentrification and push the already struggling residents out of the area, into the outer Eastern Portland and Gresham areas. Author Karen Gibson of “Bleeding Albina: A History of Community Disinvestment” explained it this way: “The occupation of prime central city land in a region with an urban growth boundary and in a city aggressively seeking to capture population growth, coupled with an economic boom, resulted in very rapid gentrification and racial transition in the 1990s.”

From 1990 to 2016, over 4000 households and more than 10,000 African American residents would be displaced from their homes as a result.

In 1996, when planners attempted to produce a similar plan for the Southwest Portland area, they faced two distinct issues. The lay of the land and various environmental issues would reduce the effects that land use planners could use in increasing the housing density in the area. But more importantly, the local community was enraged at the idea of redeveloping single family neighborhoods, and as the residents tended to be well-educated, higher income, typically white, and more organized and well-resourced than the residents in the Albina and Outer Southeast area, they succeeded in not only pushing back on almost every attempt to increase density in the area, but their work managed to derail the entire 1994 plan, forcing a shift from community planning to ‘area planning’, trying to target work in higher density areas.

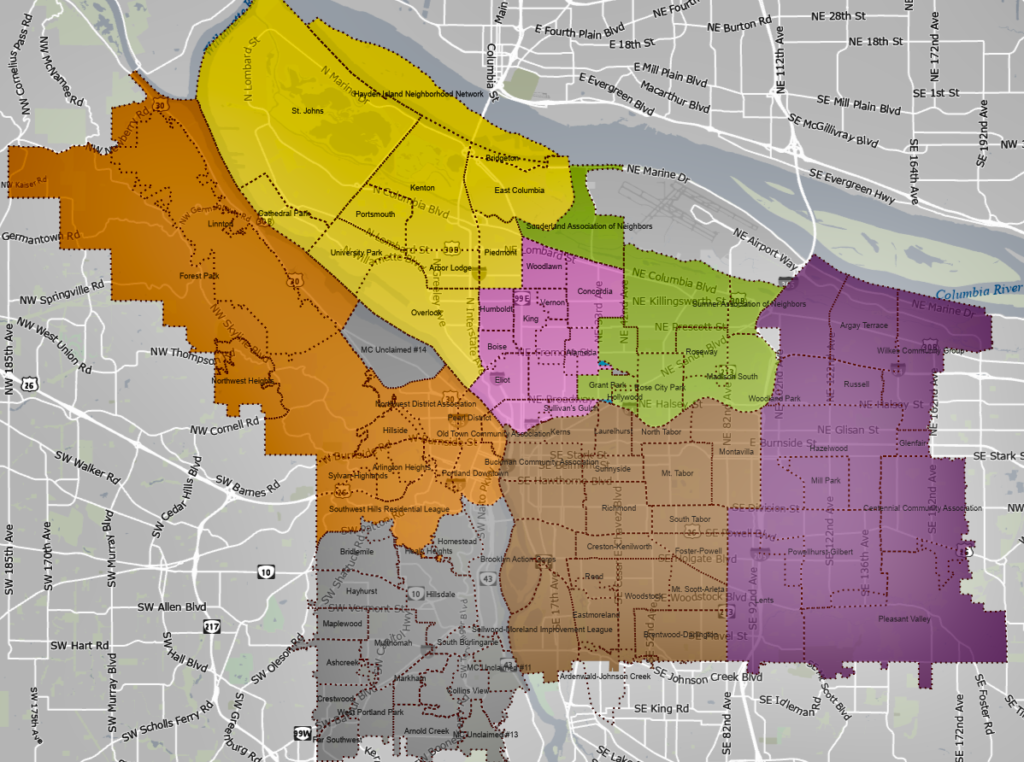

SWNI, a non-profit organization founded in 1978 specifically to fill the need the City had asked be filled with the creation of the Office of Neighborhood Associations, played heavily in this tale, the 94 volunteer led neighborhood associations coordinating with 7 ‘district coalition offices’ to work with the city’s Office of Community and Civic Life to provide input from the communities on how the citizens feel about particular events in their areas. In 2020, when this lawsuit was filed, SWNI was one of five privately run district coalitions, the remaining two run by city managed offices.

However, SWNI was no stranger to controversy of it’s own. In addition to their successful attempts to derail attempts to increase living density in the southwest area, they had also been caught up in a 2011 embezzlement case where former SWNI employee Virginia Stromer eventually pled guilty to stealing well over $130,000 of SWNI funds dating back to at least 2004, an organization that in court records claims annually about 85% of their funding comes directly from the cities Civic Life department (most of the remaining 15% came from Portland’s Bureau of Environmental Services and West Multnomah Soil & Water). The embezzlement case, of which restitution has only seen a few hundred dollars of the over $200k owed, is something SWNI seemed to actively want to ignore ever happened, even going so far as board members who were active in both 2011 and 2020 hiding it’s existence from newer board members.

In the Present Day

The background helping bring the story to the current times, Ms. Hiller-Webb joined SWNI in 2019, as a representative of one of the local neighborhood organizations, where she jumped in with fervor learning the shorthand language 20+ year veterans of the board had been using, and working to try to make the organization more equitable and justice-minded (efforts that were ultimately denied by the broader board). This was around the same time that she first met Ms. Tyvoll, at a July 2019 SWNI organized picnic, where they connected over a desire for more inclusivity and equity in the area. During this time she started noticing financial information that, as a business owner herself, didn’t make sense, and when she started asking questions, board members began acting strangely, referring to it as ‘magic money’ and refusing to justify it’s purpose or use. January 2019 board minutes confirmed that excess taxpayer funds were being transferred to different accounts to avoid having to return unused grant money (taxpayer funds) to the City, causing the questions of mismanagement of funds to deepen drastically and quickly.

It was then that Ms. Hiller-Webb was urged to connect with former SWNI Board member and attorney Jim McLaughlin (he/his) who gave in depth information about the 2011 embezzlement case, an event which had apparently caused the ouster of not only Ms. Stromer, but also the forced his own departure from the organization, the victim of a slander campaign for his attempts to uphold the law. Ms. Hiller-Webb doubled down on the public records method of trying to get information to better learn about what, if any, mismanagement of funds was happening, when COVID began interfering with the day-to-day running of all of our lives.

When the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) was released by the federal government, SWNI, knowing full well that it’s funding through the city was not impacted at all as a result of the pandemic, applied for funding, over the objections and with complete opacity to the numerous board members who asked to see the application both before it was submitted as well as after. In a declaration by Ms. Hiller-Webb, she stated that “SWNI created a Citizen Engagement Allocation Program, with the idea that it would move taxpayer-provided funds from Civic Life to a grant program that would create an artificial COVID hardship.” SWNI eventually received over $66k in federal funds, a loan which was later forgiven by the federal government. As Ms. Hiller-Webb went on to state “SWNI had more than sufficient funds to continue its operations, whereas many local businesses back in April 2020 – right after the physical distancing restrictions went into effect – had lost all their revenue stream, could not pay their employees, and were on the verge of and indeed some did shutter their doors permanently.” A move which has historically disproportionally affected BIPOC owned businesses.

SWNI created a Citizen Engagement Allocation Program, with the idea that it would move taxpayer-provided funds from Civic Life to a grant program that would create an artificial COVID hardship.

Shannon Hiller-Webb, Court Declaration

This misrepresentation, combined with complaints made to Commissioner Jo Ann Hardesty by Ms. Hiller-Webb and Ms. Tyvoll among others, in her position as lead of Civic Life, caused the city to withhold funds to SWNI pending a forensic audit. That audit, completed November 2020, came back with ‘conclusions of troubling financial mismanagement’, and in March 2021, the city officially struck SWNI from it’s list of district coalition offices, replacing it with a government run version, modeled on the two existing offices the city had already been fielding.

Public Records, Private Organization

Public records provided under state records laws may seem like strange bedfellows for a non-profit like SWNI, but as Ms. Tyvoll testified to the court, it was something that SWNI had done regularly as part of their normal business, in fact one of her earliest interactions with SWNI being responding to a public records request about an event in the area. There was no pushback from SWNI, and the neighborhood organization that was under SWNI was ‘required’ to do the same, per Ms. Tyvoll. And it was part of that confusion that reigned when, as part of the process for appealing denied public record requests, Former Multnomah County District Attorney Rod Underhill initially denied to intervene in the case. Even when he eventually realized this was a question over a District Coalition and not merely a neighborhood organization, he agreed to a hearing over it, but still didn’t quite recognize the power dynamics that existed between the district coalitions and the city, ruling that, from his understanding, because SWNI did not directly control government policies, they were not a governmental body and thus were exempt from public record laws.

A win for SWNI, to be sure, but a short lived one, as in the few months after the case was appealed to the Multnomah District court, the forensic audit finding disturbing mismanagement and the eventual defunding of SWNI by the city all but gutted SWNI’s ability to exist. They no longer held the official position as being a district coalition, and no longer had the grant funding from the city to maintain the neighborhood associations that used to be under it. Those functions were all now handled by the newly formed city-run office of Southwest Community Services . In court, SWNI tried to highlight how, because of the defunding, there was no question that they were not a government agency and in no way responsible to respond to public records requests.

Attorney Rian Peck, representing Ms. Hiller-Webb and Ms. Tyvoll, however, disagreed, pointing out specifically how the simple move of defunding and removing SWNI from the list of Portland District coalitions was enough to make the organization effectively useless, writing in their motion for summary judgement: District Coalitions are not only the City’s mouthpiece to the people about what the City has planned for their neighborhoods, but they are also the neighborhoods’ representatives and advocates to City officials,” going on to state “If SWNI’s functions were not essential to the City’s unique form of governance, the City surely would not take it upon itself to perform the exact same functions in SWNI’s absence.”

If SWNI’s functions were not essential to the City’s unique form of governance, the City surely would not take it upon itself to perform the exact same functions in SWNI’s absence.

Rian Peck motion for summary judgement

They also pointed out how, when the case was before the DAs office, SWNI relied on the City Attorney to defend them, a move that was ‘logically inconsistent with its position that it is an independent, private entity’, as well as the use the same public records law to extort money from the city for records that the city required from them, an incident where SWNI violated city standards to try to gain an additional $30,000 in revenue.

None of this was lost on the judge, apparent by the prepared notes it seemed he read from when he announced summary judgement in favor of Ms. Hiller-Webb and Ms. Tyvoll. While declaring SWNI, at the time the records request was filed, a public body for purposes of record request laws, he declined to extend the same designation to all privately operated district coalitions, citing their lack of presence in the courtroom. He did feel that his ruling would be relevant to them, however. He also ruled that SWNI improperly witheld the records requested, and ordered that they be given to Hiller-Webb and Tyvoll within 30 days, as well as awarding attorney fees.

In a prepared press release announcing the victory, lead attorney Rian Peck stated “Even though SWNI purported to represent its constituents’ interests, it refused to be transparent. Government without oversight is dangerous. I am proud to represent two of SWNI’s constituents in their hard-wrought fight for transparency.”

Ms. Tyvoll agreed, stating: “Access to public records is imperative for residents to hold City of Portland officials and those they fund and task with quasi-governmental roles accountable. My records request to SWNI was ignored and this allowed them to perpetuate and enable what the City of Portland Bureau of Planning and Sustainability (BPS) determined funded “…the historical, structural, and institutional racism that has created deep racial inequities that continue to harm Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other communities of color.”(Letter introducing the Historical Context of Racist Planning: A History of How Planning Segregated Portland). The City of Portland provided SWNI with 85% of their annual funding and has effectively perpetuated and enabled white supremacy for 40+ years.”

The City of Portland provided SWNI with 85% of their annual funding and has effectively perpetuated and enabled white supremacy for 40+ years.

Marie Tyvoll, Press Release

For an organization that’s had a historical record of misusing well over $400,000 in local and federal taxpayer money since the beginning of the 21st century, using it’s position to prop up predominantly white homeowner neighborhoods at the expense of the rest of the city, it seems that this may well be the closing of one of the final chapters of the organization. Even so, to look at SWNI’s website, they currently make no effort to acknowledge their status as an unofficial district coalition, effectively burying their heads in the sand and hoping the controversies will one day blow over.